Good Fats

Variations in Fat

In my biochemistry doctoral dissertation and studies, I specialized in "bad" fats and fatty acids, with a special emphasis on how fatty acids might initiate plaque in arteries (via inflammation). But fats can be good in a variety of ways.

For one, fats are important because toxins are often stored in fat cells (including the fat cells of animals we eat).

Toxin storage, in fat, can be good. It slows toxic effects. You don't want your sensitive brain cells killed by toxins - pack them away in the fat! However, this becomes very bad if we are continuously eating, and therefore storing, toxins.

A vivid example of this is the antipsychotic drug called Clozapine. This drug, Clozapine, is often perceived by the body as a toxin (whether it is toxic or not). This bodily perception causes rapid growth and development of protective fat cells, which store it. Next up...rapid weight gain. The weight gain will be followed by metabolic problems from inflammatory molecules - fat cells constantly secrete inflammatory molecules into the blood (it's just what fat cells loaded with toxins do) (ref). Realize: because of these inflammatory secretions, fat is actually considered an endocrine organ by scientists (endocrine meaning "a system that secretes bioactive molecules", a classical example being your adrenal glands which secrete adrenaline) (ref).

Now - and this is important - within dietary fats, there are clearly "good" fats and "bad" fats, as well as what I call "neutral" fats. Neutral fats can be either be used for good purposes, like energy, or bad purposes, like massive fat stores, by your body. Most fats we eat are fairly "neutral", unless we cook them and oxidize them, thus making them bad. (Stop cooking your olive oil!)

To me, one of the most interesting aspects of eating different fats is how rapidly and drastically they can change your body and mind. If you eat a grass-fed steak, for example, the proteins won't be significantly different than the proteins in corn-fed steak. The proteins will be built from the same 20 amino acid "building blocks" that will be broken down by your digestive system into those individual 20 amino acids (unless you have a leaky gut, which is a different issue). However, if you eat butter (fat) from corn-fed cows versus butter from grass-fed cows, the fat composition will be drastically different (ref). This means the fat will affect your body drastically differently.

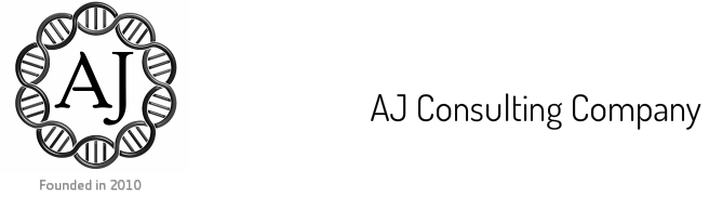

For instance, in a "fat composition" study (ref), fresh grass in cattle diets cut the human nutritional "atherogenicity index" in half. This is because corn oil ("corn fat") is made up of over 80% fatty acid tails that are 18-carbons long (ref) - see the 18-carbon oleic acid in the image below [note: carbons are represented by shorthand "joints" in the molecular structures]. Corn also is less than 1% DHA. On the other hand, a grass called "star grass" (a randomly selected grass example), has less than 30% fatty acid tails that are 18-carbons and about 20% fatty acid tails that are 22-carbons long - mostly DHA (ref). This means corn and grass are radically different, with radically different fat compositions.

For one, fats are important because toxins are often stored in fat cells (including the fat cells of animals we eat).

Toxin storage, in fat, can be good. It slows toxic effects. You don't want your sensitive brain cells killed by toxins - pack them away in the fat! However, this becomes very bad if we are continuously eating, and therefore storing, toxins.

A vivid example of this is the antipsychotic drug called Clozapine. This drug, Clozapine, is often perceived by the body as a toxin (whether it is toxic or not). This bodily perception causes rapid growth and development of protective fat cells, which store it. Next up...rapid weight gain. The weight gain will be followed by metabolic problems from inflammatory molecules - fat cells constantly secrete inflammatory molecules into the blood (it's just what fat cells loaded with toxins do) (ref). Realize: because of these inflammatory secretions, fat is actually considered an endocrine organ by scientists (endocrine meaning "a system that secretes bioactive molecules", a classical example being your adrenal glands which secrete adrenaline) (ref).

Now - and this is important - within dietary fats, there are clearly "good" fats and "bad" fats, as well as what I call "neutral" fats. Neutral fats can be either be used for good purposes, like energy, or bad purposes, like massive fat stores, by your body. Most fats we eat are fairly "neutral", unless we cook them and oxidize them, thus making them bad. (Stop cooking your olive oil!)

To me, one of the most interesting aspects of eating different fats is how rapidly and drastically they can change your body and mind. If you eat a grass-fed steak, for example, the proteins won't be significantly different than the proteins in corn-fed steak. The proteins will be built from the same 20 amino acid "building blocks" that will be broken down by your digestive system into those individual 20 amino acids (unless you have a leaky gut, which is a different issue). However, if you eat butter (fat) from corn-fed cows versus butter from grass-fed cows, the fat composition will be drastically different (ref). This means the fat will affect your body drastically differently.

For instance, in a "fat composition" study (ref), fresh grass in cattle diets cut the human nutritional "atherogenicity index" in half. This is because corn oil ("corn fat") is made up of over 80% fatty acid tails that are 18-carbons long (ref) - see the 18-carbon oleic acid in the image below [note: carbons are represented by shorthand "joints" in the molecular structures]. Corn also is less than 1% DHA. On the other hand, a grass called "star grass" (a randomly selected grass example), has less than 30% fatty acid tails that are 18-carbons and about 20% fatty acid tails that are 22-carbons long - mostly DHA (ref). This means corn and grass are radically different, with radically different fat compositions.

Saturation & Oxidation

Now, no discussion about good/bad/neutral fats would be complete without a simplified explanation of saturated versus unsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid omega numbers.

Saturation is simple: saturated fatty acids have no double bonds (double lines), as seen in palmitic acid and caprylic acid above. These can be good sometimes and bad sometimes. Neutral, as I say. Much of what people have heard about saturated fat being "bad" is marketing plus exaggeration (as marketing usually is). In fact, if you are cooking, saturated fats are the ones to use. Coconut oil would be a good example of an excellent fat to use in cooking because it contains mostly saturated fatty acids.

Unsaturated fatty acids have one or more double bonds. These can also be either good or bad. For instance, the presence of double bonds makes unsaturated fatty acids vulnerable to oxidation where oxygen molecules attach to the site of the double bond (see image above). Heating is especially problematic since heating unsaturated fatty acids (e.g. olive oil) accelerates oxidation at any double bond sites. In fact, I only recommend cooking with coconut oil (refined or unrefined), since coconut oil is mainly small, saturated fatty acids (like caprylic acid shown above) that cannot oxidize and are good for your metabolism. I will further explain this below.

I can't stress enough that eating oxidized fatty acids is nearly always bad and is becoming increasingly recognized as hazardous to our health. Rabbits fed oxidized fatty acids, for example, had a 100% increase in artery pre-plaques ("fatty streak lesions") (ref). I've even personally published work on the oxidized fatty acid HODE (18:2); a nasty component found within arterial plaques (ref).

When you digest and metabolize (use for energy/burn) saturated or unsaturated fatty acids, there is not much difference. Your body uses one extra enzyme and one additional "step" when burning unsaturated fatty acid (Enoyl CoA Isomerase) but this extra step does not significantly burn more energy. Making cholesterol from fatty acids requires over 20 steps, so something like that would be a significant energy sink (in biology).

So really, the story of saturated versus unsaturated is fairly simple. At least for now.

Saturation is simple: saturated fatty acids have no double bonds (double lines), as seen in palmitic acid and caprylic acid above. These can be good sometimes and bad sometimes. Neutral, as I say. Much of what people have heard about saturated fat being "bad" is marketing plus exaggeration (as marketing usually is). In fact, if you are cooking, saturated fats are the ones to use. Coconut oil would be a good example of an excellent fat to use in cooking because it contains mostly saturated fatty acids.

Unsaturated fatty acids have one or more double bonds. These can also be either good or bad. For instance, the presence of double bonds makes unsaturated fatty acids vulnerable to oxidation where oxygen molecules attach to the site of the double bond (see image above). Heating is especially problematic since heating unsaturated fatty acids (e.g. olive oil) accelerates oxidation at any double bond sites. In fact, I only recommend cooking with coconut oil (refined or unrefined), since coconut oil is mainly small, saturated fatty acids (like caprylic acid shown above) that cannot oxidize and are good for your metabolism. I will further explain this below.

I can't stress enough that eating oxidized fatty acids is nearly always bad and is becoming increasingly recognized as hazardous to our health. Rabbits fed oxidized fatty acids, for example, had a 100% increase in artery pre-plaques ("fatty streak lesions") (ref). I've even personally published work on the oxidized fatty acid HODE (18:2); a nasty component found within arterial plaques (ref).

When you digest and metabolize (use for energy/burn) saturated or unsaturated fatty acids, there is not much difference. Your body uses one extra enzyme and one additional "step" when burning unsaturated fatty acid (Enoyl CoA Isomerase) but this extra step does not significantly burn more energy. Making cholesterol from fatty acids requires over 20 steps, so something like that would be a significant energy sink (in biology).

So really, the story of saturated versus unsaturated is fairly simple. At least for now.

Omegas

|

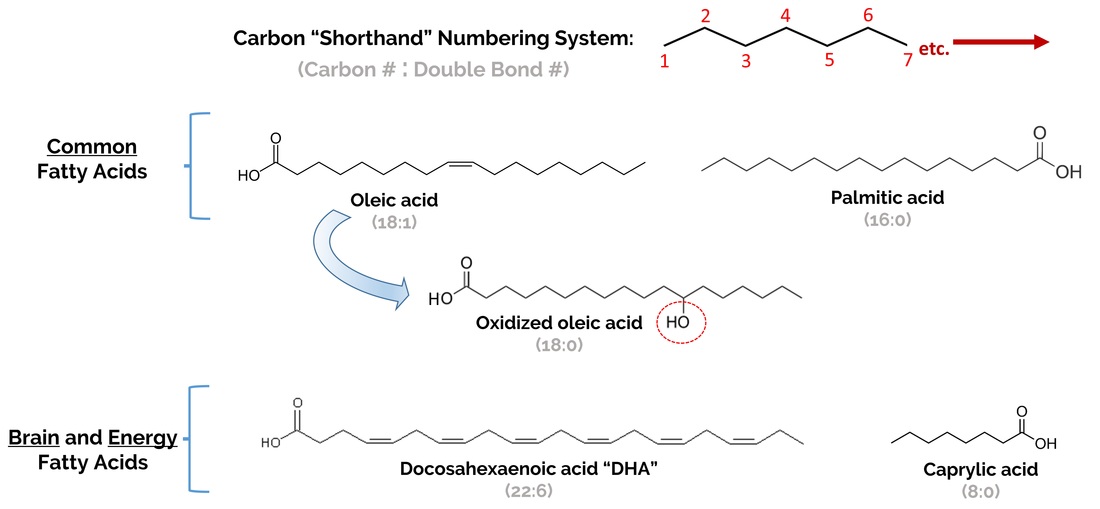

How omega numbers are derived is shown here on the right; it is simply a question of where the "tail" end double bond is positioned.

The omega double bond is important because many omega-6 fatty acids (like the arachidonic acid pictured) are usually "pro-inflammatory" while many omega-3 fatty acids are "cardioprotective" (ref) - the opposite of inflammatory - in addition to other healthful omega-3 functions. It has been speculated that the problem with omega-6 fatty acids is that our ancestors ate a similar ratio of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids while we currently eat mostly omega-6. |

Speculation or not, our modern omega-3/-6 imbalance is indeed a problem, especially for our brains (as discussed in "Smart Supplementing" under DHA). For simplicity, let's just think about DHA (although eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA], alpha-linolenic acid [ALA], and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) omega-3's are interesting as well). Since our dominant industrial crops - corn and soybeans - have virtually no DHA, your body is being forced to predominantly create its own DHA. This doesn't lead to "deficiencies", depending on how you might define "deficiency", but the modern diet certainly leads to sub-optimal levels of DHA.

Why do you want loads of DHA?

In "Smart Supplementing" under "DHA", the importance of this fatty acid for your brain is highlighted and it is noted that DHA is a major structural component of brain tissue, comprising 30% of mammalian gray matter neuronal membranes (ref). This is why human breast milk contains a significant amount of DHA and increased DHA content in breast milk consistently improves children's cognitive test performances in samples from 28 countries (ref).

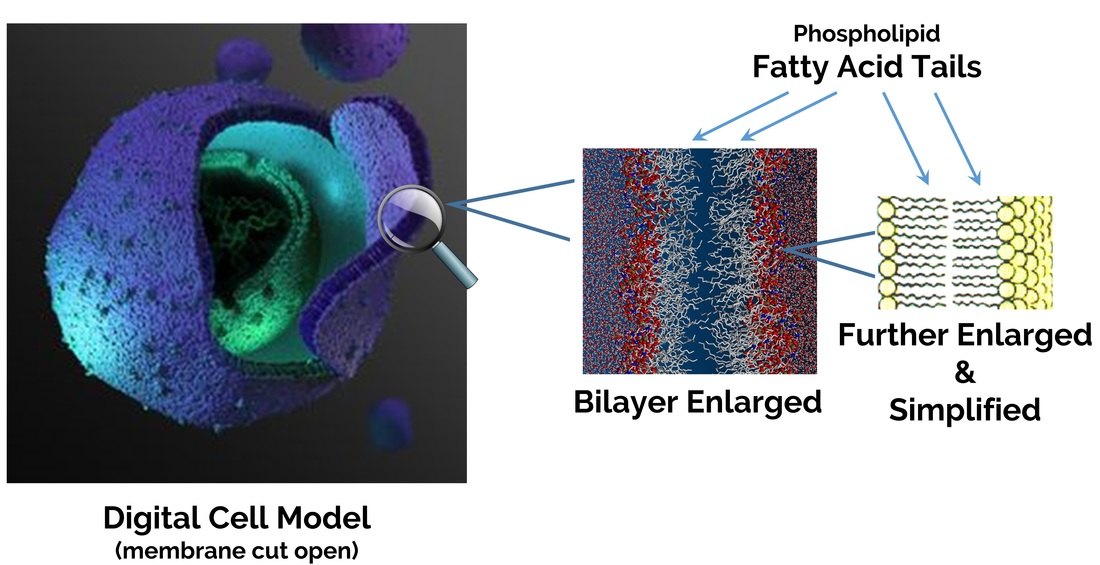

Side story: when a phrase like "structural component" is used above, it basically means the cell membranes. Since our brains and bodies are packed with cells (all of which have membranes) we have billions of fatty acid tails forming bilayers around cells (called "phosopholipids" because of a phosphate attached to these fatty acid "lipid" tails).

See the single cell image below to help envision the sheer quantity of fatty acid tails surrounding cells throughout your entire body.

Why do you want loads of DHA?

In "Smart Supplementing" under "DHA", the importance of this fatty acid for your brain is highlighted and it is noted that DHA is a major structural component of brain tissue, comprising 30% of mammalian gray matter neuronal membranes (ref). This is why human breast milk contains a significant amount of DHA and increased DHA content in breast milk consistently improves children's cognitive test performances in samples from 28 countries (ref).

Side story: when a phrase like "structural component" is used above, it basically means the cell membranes. Since our brains and bodies are packed with cells (all of which have membranes) we have billions of fatty acid tails forming bilayers around cells (called "phosopholipids" because of a phosphate attached to these fatty acid "lipid" tails).

See the single cell image below to help envision the sheer quantity of fatty acid tails surrounding cells throughout your entire body.

So if you actually read all of that, you basically grasp the concept of a fatty acid. Also, how prevalent "fats" (fatty acids) are in your body (every cell membrane). They also link up together (in 3's, forming "triglyceride) to form actual fat stores in your adipocyte cells throughout your body.

Cholesterol (another "fat" or lipid) is also packed into these cell membranes by the millions but we'll save cholesterol for a bright new day. Since cholesterol is the ingredient for "steroid" hormones and it is tremendously important in your brain, that can of worms will need to be kept closed on this page.

So what should you eat? Well, in a study of people eating "diverse" diets from Italy, Finland, and the USA the fatty acid tails from the cell membranes (testing/measuring red blood cells since those are the easiest to obtain) were comprised of +50% 18-carbon fatty acid tails and +30% 16-carbon fatty acid tails (ref). This is common. That's what you should not eat - at least too much.

How can you avoid these popular fats? As we eat our modern food derived from processed corn and soybeans - including the chicken and beef that also ate corn and soybeans - we end up with mediocre 16- and 18-carbon fatty acids. Remember: they aren't necessarily "bad" but they aren't really "good" either (like DHA or the medium-chain fatty acids) - unless you start cooking the fatty acids containing double bonds and turn them into artery plaque starter.

Just don't settle for "subsistence", seek "optimal". Research the benefits of individual fatty acids - numerous types exist and information is easy to find (now that you know about fatty acid "chain length" [such as 18-carbon, etc.]) - and be sure lots of good fat. Feed your brain! The good is the enemy of the best, if it keeps us from attaining the best.

Ever Upward.

Cholesterol (another "fat" or lipid) is also packed into these cell membranes by the millions but we'll save cholesterol for a bright new day. Since cholesterol is the ingredient for "steroid" hormones and it is tremendously important in your brain, that can of worms will need to be kept closed on this page.

So what should you eat? Well, in a study of people eating "diverse" diets from Italy, Finland, and the USA the fatty acid tails from the cell membranes (testing/measuring red blood cells since those are the easiest to obtain) were comprised of +50% 18-carbon fatty acid tails and +30% 16-carbon fatty acid tails (ref). This is common. That's what you should not eat - at least too much.

How can you avoid these popular fats? As we eat our modern food derived from processed corn and soybeans - including the chicken and beef that also ate corn and soybeans - we end up with mediocre 16- and 18-carbon fatty acids. Remember: they aren't necessarily "bad" but they aren't really "good" either (like DHA or the medium-chain fatty acids) - unless you start cooking the fatty acids containing double bonds and turn them into artery plaque starter.

Just don't settle for "subsistence", seek "optimal". Research the benefits of individual fatty acids - numerous types exist and information is easy to find (now that you know about fatty acid "chain length" [such as 18-carbon, etc.]) - and be sure lots of good fat. Feed your brain! The good is the enemy of the best, if it keeps us from attaining the best.

Ever Upward.

Dr. Jay

...continue learning: SMART SUPPLEMENTING